The last feats of Theseus concern the period between the realization of equality and the descent into body consciousness.

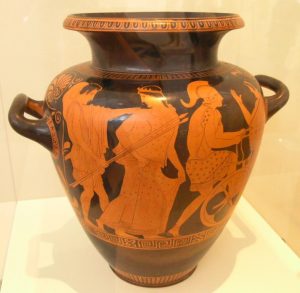

Theseus leading Helen to a chariot arranged by Peirithoos – National Archaeological Museum of Athens https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/f5/NAMA_18063_Helene_Ph%C5%93be.JPG

To fully understand this web page, it is recommended to follow the progression given in the tab Greek myths interpretation. This progression follows the spiritual journey.

The method to navigate in the site is given in the Home tab.

Theseus and the Amazons

With the assistance of his friend Pirithoos, Theseus abducted the Amazon Antiope, who according to some authors was their queen. Other sources name her Hippolyte. To avenge this rape, or to punish the insult inflicted upon Antiope when Theseus abandoned her to wed Phaedra, or else because Antiope had fallen in love with him and had thus disrespected the rules of her people, the Amazons opened an attack on Athens. Antiope perished in the ensuing battle.

As the king of Athens, Theseus is the representative of the main actions induced by the inner guide in the structuring of inner growth which follows the first great experience of inner contact (Athena, the master of yoga, is the patron goddess of Athens, of which Theseus is the tenth king).

Theseus therefore naturally participates in all the Panhellenic adventures which follow the quest of the Golden Fleece till the psychic being come to the front, not only in the Calydonian Boar Hunt, but also, in the same fashion as Heracles, in a battle against the Amazons. Let us remember that Bellerophon, who was the one to achieve a victory over Chimera (illusion), had also fought against these warrior women.

Diodorus includes Theseus in the group accompanying Heracles, even though in the most ancient accounts by Pindar and Pherecydes the expeditions of the two heroes were held separately. Whether they were held separately or together is of little importance for the purpose of this study, as they simply describe the same realisation from two different points of view represented by the two different genealogical lineages.

This battle of Theseus against the Amazons allows to specify an important point in the effort of mastering the primary vital energies symbolised by the boar hunt. It is a detachment which must arise naturally rather than as a result of the will acting by principle through either rejection or constraints, as noble as may seem the action of this will. For it is not the death of Melanippe, an heroin who illustrates a constraint applied to a certain energy which then deviates in the seeker (she is mentioned only in a reconstituted portion of the Library of Apollodorus, in which Theseus takes part in Heracles’ expedition). Rather, it is a question of the death of Hippolyte, which is to say of the very principle of dissociation through which the seeker attains sainthood, for Hippolyte in fact represent ‘vital energy from which one separates oneself’.

In this study we will not take up in detail the symbolism of the Amazons, which was developed during the study of the ninth labour of Heracles and explores the themes of the culmination of the psychic fire at the mouth of the river Thermodon, ‘the fire of union’.

This group of female warriors did in fact dwell beyond the Propontis (the sea of Marmara), ‘an advanced work on the vital’ (Pro-Pontos), on the shores of Pont-Euxin, ‘a very strange and inhospitable vital’. Their capital was situated at the mouth of the river Thermodon, ‘the heat or ardour of union’, which marks the ultimate phase of progression towards a union with the Divine (often known as ‘uniting life’), the culminating point of the growth of the inner fire. As the Amazons were all women, they represent a realisation rather than an effort at work. Some authors describe them as accomplished horsewomen, which demonstrates a perfected vital mastery; the seeker is not only ‘a master within his own domain’, but is also an accomplished wise man and saint. This realisation opens the doors to the powers of life which will be entirely acquired in the following labour of Heracles, that of the Cattle of Geryon. It is in this region of spiritual progression that Heracles will erect the famous pillars marking the limits which the initiates of that period believed to be impassable (these represented the transformation of the physical mind). It is possible to associate this work with the end of the second phase of yoga in accordance with Sri Aurobindo’s teachings, which is the end of spiritual transformation following psychic transformation.

As in Heracles’ case, it is a romantic episode which brings about the beginning of this adventure. This hero had actually formed a friendship with the Amazons and received a magical girdle from them during the peaceful time before they fought in battle. But still attracted by the ‘great heights of the ideal’ and an immersion into the silence of the Self, Theseus abducted the Amazon Antiope, or Hippolyte.

The change of the name Antiope most probably originated from the need to clarify its meaning. Hippolyte can be understood without undue ambiguity as ‘the vital energy from which one separates oneself’. On the other hand, the interpretation of the name Antiope is more uncertain, due to the numerous possible meanings of ‘anti ‘. As in this context it is associated with Hippolyte, it can be understood as ‘an opposite view’.

Theseus’ reversal of attitudes from love to war therefore indicate that the seeker must first acquire the capacity to consider ‘a different point of view’ so as to surpass the state of liberation in the spirit and access the next stage of the liberation of the modes of Nature and of dualities.

The seeker who has been successful in an immersion in the Self is no longer in search of any goal, and no longer considers any work of yoga to be necessary (men and even male children are rejected by the Amazons).

In the labours of Heracles we have seen that the distortion of a rightful adherence to an ideal, due to dogmatic excess followed by a lack of adaptation or rigidity by principle, could lead to a distorted or perverse energy (Melanippe). The very principle of the separation between spirit and matter can in fact bring with it all kinds of distortions and deviations.

Theseus and Hippolytus (in this context, the son of the queen of the Amazons).

Theseus wed Phaedra, the daughter of Minos, who bore him two children, Demophon and Acamas (it is sometimes said that they were actually the sons of Antiope).

Then Phaedra fell in love with and made overtures to Hippolytus, the son who Theseus had fathered in his union with the queen of the Amazons. But the former refused any tie with a woman, and rejected her advances. Phaedra then accused him of having raped her and brought her case to Theseus, who asked Poseidon to put an end to the life of the accused. Poseidon caused a great bull to spring forth from the waves, which frightened the horses of Hippolytus and resulted in his death.

When the seeker progresses on the path of purification, when he has put an end to the mind’s pretension to seize spiritual realisation as its own (symbolised by the struggle against the Minotaur) and ceases to believe that the realisations of wisdom and sainthood are the crowning achievements of the path (the Athenians – the actions of the inner master -, have vanquished the Amazons), then he can more actively advance in the direction of joy. This is signaled by Theseus’ union with Phaedra, ‘the joyful, the shining’.

But there remains however a ‘memory’ of an ancient attraction for an ideal that is beyond matter, a memory which must still be purified (the attraction of Theseus for the Amazons, which continues with Hippolytus). What has already been surpassed by the victory over the Amazons imposes itself newly upon the seeker under a different aspect, which is however narrowly tied to the first. Hippolytus, the fruit of the union of Theseus and Antiope, constitutes despite himself an obstacle to true joy, to the union of Theseus and Phaedra.

This story has been handed down to us in detail only through the texts of Euripides, which must be considered with great reservation.

Hippolytus, ‘vital energy from which one separates oneself’, characterises the kind of seeker who creates a division between a liberation in the spirit and an incarnation in which the energies of life are at play. He is in fact the son of an Amazon, and the grandson of Ares.

Hippolytus’s veneration of Artemis, the goddess of purification, and his rejection of Aphrodite, ‘love in evolution’, confirms this attachment to a form of partial purity obtained through rejection, denial or amputation.

Phaedra ‘the joyful’ strives to bring back towards herself this amputated energy, but it is also apparent that this energy is incapable of orienting itself towards true joy.

The seeker must put an end to error and set himself moving again. To detach from an ancient ideal and surpass the attainments of wisdom and sainthood, he calls upon the subconscious forces; by asking Poseidon to slay his son, Theseus echoes the origins of the Trojan War. A reply is given to him in the surge of an impulse of power of the luminous mind which gravely perturbs the forces sustaining one who is divided from life (the god caused a great bull to surge forth from the waves, which frightened the horses of Hippolytus and led to the latter’s death).

The will to escape from incarnation into the higher realms is thus put to an end, so that a descent into the body may begin. This is not the work of Theseus however, who has completed his task of a double psychic and spiritual realisation. This is why according to numerous authors, Theseus and Pirithoos fail in their attempted abduction of Persephone.

To confirm that this is indeed the end of Theseus’ mission, Hellanicus, a mythographer of the fifth century BCE, specifies that this hero was fifty years of age at the time of Helen’s abduction. Fifty symbolises completion in the world of forms, and was perhaps also considered to be an advanced age at the time.

The hanging of Phaedra, the daughter of Minos, seems sufficiently surprising for us to consider it to be a later invention. If it was mentioned in early sources, it would have to be deduced that she only represents a first stage of the realisation of joy, and that her task being fulfilled she could then end her life.

The abduction of Helen, and the attempted abduction of Persephone

Theseus and Pirithoos had both taken part in previous unions, the former with Phaedra and the latter with Hippodamia. But as they were half-gods and sons of Poseidon and Zeus respectively, they aspired to claim as their spouses two daughters of the gods. Some sources claim that both of their wives had died, and that they had agreed to randomly select from between the two of them who was to wed Helen. The winner would then have to help the loser court and win the wife of his choosing. Theseus was chosen by fate to claim Helen, and in his turn Pirithoos chose Persephone as his desired future wife.

They proceeded to abduct Helen, who according to several sources was then but ten years of age. Theseus then entrusted her to the care of his mother Aethra so as to be able to accompany his friend Pirithoos into Hades.

(Some authors claim that it was Idas and Lynkeus who carried out the abduction, while others claim that Tyndareus himself entrusted Helen to Theseus).

Having set out in search of their sister, the Dioscuri Castor and Pollux ravaged Attica and freed Helen, taking Aethra away with them as well.

Accounts differ greatly from the point of Theseus and Pirithoos’ descent into Hades.

In the Odyssey, it is stated that Ulysses hoped to meet his two friends there, which suggests that they remained in the underworld eternally. Virgil and Diodorus are in agreement with this version.

The first to mention the liberation of Theseus by Heracles is Euripides, an author who we approach with caution.

Later accounts indicate that the heroes were bound in chains in Hades, and Apollodorus even describes them on a ‘seat of forgetting’. In some accounts, the seat bore into their flesh over time, and their bonds were made of snakes.

Other versions tell of the liberation of Theseus by Heracles, or sometimes of the liberation of the two friends, while yet another version claims that Pirithoos was devoured by Cerberus.

If it is assumed that the deaths of the heroes’ first two wives are not only mentioned to justify the possibility of other unions, then they probably indicate that previous goals had been attained, namely vital mastery (Hippodamia), and a stable inner joy obtained through an appropriate consecration (Phaedra, daughter of Minos).

Just as the story about Theseus and the Amazons constitutes an alternative approach to the ninth labour of Heracles, or rather a practical example of a theoretical principle, Helen’s abduction by Theseus is in this study considered in parallel to that perpetrated by Paris-Alexander. However, the difference in time scale, the ambition of the heroes (a desire to claim the wife of Hades), and the presence of Idas and Lynkeus in finding Helen (they died before the Trojan War) indicates that this is only the defeat of a first attempt.

The seeker has reached a transformation to a certain extent; a new phase of work is therefore opened to him. However, he does not know with which part of his being to pursue the path towards greater freedom (Helen). He either strives with his inner consciousness (Theseus), or else through a yogic effort in incarnation (Pirithoos, ‘a pointed effort’ or ‘one who experiments swiftly’). But he is not yet able to make this choice at that moment (fate chooses otherwise for the two heroes).

With Theseus having abducted Helen, it is the movement of going inside which will be the principal element of the quest for a deepened liberation (Helen), the effort having to be abandoned to the hands of the Absolute.

It would also appear that this future evolution is linked to the work in the corporeal inconscient, which must be rendered conscious even if the way in which it is thought to be carried out is unrealisable (Pirithoos chooses to wed Persephone, the goddess who oversees the work of connecting and linking). Even if the aim is valid, the method is flawed by unconsciousness and the remains of the ego; no effort carried out by the seeker alone can carry out this new yoga.

Helen is the daughter of Zeus and Leda, ‘a realisation of union through liberty’. Her age is only specified by Hellanicus, most probably only for the purpose of situating this first attempt about a decade before the Trojan War, which is to say a symbolic half-generation.

When it is Idas, ‘a vision of the whole’, and Lynkeus, ‘intuitive discernment or detailed vision’ who are said to be the ones to abduct Helen, one must understand that it is the mind which, having arrived to its highest summits in both its intuitive and discriminating aspects, perceives the direction of evolution.

In the version in which Helen is entrusted to Theseus by Tyndareus – a descendant of Taygete of the royal lineage of Sparta, representing ‘that which is sowed in’ and thus a symbol of the plane of the intuitive mind preceding the overmind – it is the surging forth of the New which takes charge of directing the quest, a progression which is perfectly coherent.

Before attempting this first descent into the body, inner consciousness entrusts its quest for freedom to the care of its ‘illumined consciousness’; the most illumined aspect of the mind remains the best guarantor of protection on the path (before the descent into Hades, Theseus entrusts Helen to his mother’s care).

In one version of the story, it is the Dioscuri Castor and Pollux – whose names signify ‘the struggle for purity in an incarnation through mastery’ and ‘sweetness, or softness’ respectively, and who are sons of Leda and brothers or half-brothers of Helen- who put an end to the first attempt by ravaging Attica, and rescue Helen so as to turn the yogic process back to a right direction.

The imprisonment of the two friends in Hades marks the end of the myths linked to Theseus, and the seeker’s need to begin a new phase of yoga. The “conscious” descent into the body is not yet possible. And in fact, Theseus and Pirithoos are not yet in a position to bring into consciousness that which has been engraved in the inconscient; they remain bound to their ‘seat of forgetting’.

In the version of the story in which Theseus is liberated, or that in which Pirithoos is devoured by Cerberus, the respective authors probably wished to indicate the end of this effort while simultaneously maintaining the movement of yoga from within the being.

Theseus’ end, and the last kings of Athens

Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex seems to confirm Theseus’ return from Hades. But as the death of Oedipus occurs before the Theban Wars, which describe the advanced process of purification of the chakras, we can inversely deduce from this that the episode of the descent into Hades has not yet taken place.

Supposing that Theseus was freed from Hades, his death, as is often the case in mythology, was not mentioned by other authors. Aristotle mentions that he was killed by Lycomedes, ‘a dominating nascent light’. According to Apollodorus and Pausanias, Lycomedes was only the cause for his death, but this hardly makes a difference.

Menestheus, ‘a powerful will’, was said to have ousted Theseus from his place on the throne before having helped to bring about his death. But he did not rule for long, for he was deposed in his turn by the sons of Theseus, Acamas ‘the tireless’, or ‘he who is effortless’, and Demophon, ‘a penetration of consciousness into numerous areas of the being’. Thus, the personal will can no longer claim to dominate the quest.

Demophon was one of the last notable Athenian kings. He and his brother are a link with the Trojan War, for they later travel there in the hopes of liberating their grandmother Aethra. She had been imprisoned by Castor and Pollux when they had reclaimed Helen after Theseus’ abduction of the latter. According to some sources she had become Helen’s slave, and had accompanied her to Troy out of her free will.

In fact, the clarity of consciousness which illuminates the first phase of the path is attenuated when the seeker, still on a quest for mastery, only wishes to conquer freedom in the heights of the spirit, and refuses the material (in Troy, Aethra became the slave of Helen).

Pausanias lists a few other Athenian kings: Oxyntes, ‘he who is sharp’, Thymoetes, ‘the soul turned towards the spirit’, son and grandson of Demophon, and an usurper, Melantheus, ‘a deceptive inner guide’ succeeded by his son Codrus, who was according to Pausanias the last Athenian king. This genealogy seems to indicate a deviation in aspiration, and echoes the story of the goatherd Melanthios, who is an incarnation of this deviation in the Odyssey. The works of Pausanias must be considered very guardedly however, for they are not corroborated by earlier sources.